Michael Collings

Posted: January 16, 2003

_

I recently spoke to Michael Collings, the author of Horror Plum's and other books about King. Here is what he said

I recently spoke to Michael Collings, the author of Horror Plum's and other books about King. Here is what he saidLilja: Hi Michael. First let me thank you for doing this interview. I'm really happy to get this chat with you.

Lilja: Who is Michael Collings? What do you do for a living besides writing books about Stephen King?

Michael Collings: In 'real life' I am a professor of English at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California. Actually I have three titles, each with a slightly different responsibility. As professor of English, I teach British literature, emphasizing the 16th and 17th Centuries; my area of specialization is Milton and the Epic-hence my interest in the epic quality of King's writings. As Director of Creative Writing I administer and teach in the CW program; my main interest here is poetry-and again, hence my interest in King's each poetry. And as Poet in Residence at Seaver College for the past six years, I present poetry readings and generally encourage greater interest among my students for poetry. To fill out my time, I design and make wire-wrapped jewelry (I've been the featured artist for WIRE ARTIST magazine, an international trade journal; and a number of my pieces have been showcased there), play the organ for my church, and write poetry.

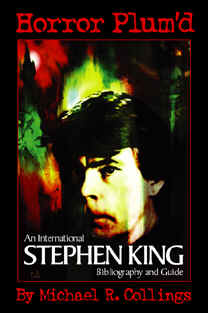

Lilja: When I read Horror Plum'd I sensed that it was made for the really die-hard King fan. The one that what's to know everything about King's work. Was that your intention?

Michael Collings: You are certainly correct in thinking that Horror Plum'd is not just 'another book about Stephen King.' But at the same time, I hope that it has interest for more than just the die-hards. It is also intended for students of King's works (high-school students looking for material for term papers, college students interested in genre literature and popular culture), for scholars writing about him, and for anyone interested in a book that demonstrates how influential a part of our times and our culture he has become. In the narrowest sense, it is almost a sociological study of the way he exports American society throughout the world; in a wider sense, it suggests how remarkably well received his stories are throughout the world.

Michael Collings: You are certainly correct in thinking that Horror Plum'd is not just 'another book about Stephen King.' But at the same time, I hope that it has interest for more than just the die-hards. It is also intended for students of King's works (high-school students looking for material for term papers, college students interested in genre literature and popular culture), for scholars writing about him, and for anyone interested in a book that demonstrates how influential a part of our times and our culture he has become. In the narrowest sense, it is almost a sociological study of the way he exports American society throughout the world; in a wider sense, it suggests how remarkably well received his stories are throughout the world.Lilja: How did you researched for Horror Plum'd? It's a lot (to say the least) of info in the book and it must have taken some time to gather it all, right?

Michael Collings: Oh, yes! This book has been nearly fifteen years in the making. It started out as part of the original Starmont series I wrote around 1985-1990. After writing a number of individual volumes (Stephen King as Richard Bachman, The Many Facets, The Shorter Works, etc.), I agreed to do a final volume devoted to bibliography-The Annotated Guide to Stephen King. The title described the book nicely; it was intended more as a guide than a full-fledged bibliography, with entries and brief discussions for all of his published writings. Several years later, Ted Dikty, then publisher of Starmont House, transferred copyright of the guide to Rob Reginald at Borgo Press, who asked me to enlarge it for his series. The Work of Stephen King appeared in 1996, a decade after the original guide. For it, I rearranged all of the initial material into a new format, then brought the data up to date, including both works by King and works about him. Already the task had become daunting; the book ended up about 500 pages long (using very small print). Borgo had designed the format so that the bibliographies could be updated with a minimum of effort, so I had kept current with new information about King, assuming that there would eventually be a revised edition. Instead, Borgo closed its doors, leaving me with a huge stack of new material an nowhere to market it.

About that time, Dave Hinchberger of Overlook Connection arranged for me to complete a bibliography he had begun of the works of Peter Straub. He published Hauntings in 1999. We followed that up with a full, annotated, definitive bibliography of Orson Scott Card, author of the popular Ender's Game and other novels. Card is one of my favorite writers, and I had been collecting bibliographic data on him for as long as I had been working with King. In 2001, OCP published Storyteller, the international guide to Card's works.

Then we decided to tackle the "biggie"-a revised, updated, completed version of the King bibliography. We originally intended to catalogue both primary and secondary works (works by King and works about him), but it became obvious that the resulting book would simply be too long to be practical. So, for the first time, I concentrated exclusively on King's writings and opened the book up to international editions as well. Much of the actual research was done through the internet, using such resources as the Library of Congress, the British Library, and various national libraries throughout Europe and South America, plus publication records from many companies and invaluable help from King fans across the globe. When Horror Plum'd appeared in late 2002 (publication date: January 2003), it intended to provide an intensive study of King's publications for over a quarter of a century, closing with the year 2002. Again, however, the format allows for additions, so if need be, it can be revised and updated further.

Lilja: You have done several books about King. Is there any kind of book about King or his work that hasn't (in your opinion) been written yet or have all aspects of his work and person been examined?

Lilja: You have done several books about King. Is there any kind of book about King or his work that hasn't (in your opinion) been written yet or have all aspects of his work and person been examined?Michael Collings: Without a doubt, King is among the most closely scrutinized of contemporary writers. Some years ago I mentioned to a colleague here that I was working on a 500-page bibliography of King, and he just stared at me. "Five hundred pages? For a living author?" He was stunned at the degree of interest King engenders.

And perhaps he was right to be so startled. I originally intended a follow-up volume to Horror Plum'dthat would concentrate on works about King; by now, I'm not sure I could handle the project...there is simply so much out there that it is intimidating even to contemplate. I'm used to doing research on people like Shakespeare and Milton, about whom there have been literally shelves of books written. King might not yet have as many titles associated with his name, but he's getting there. I'm really not sure that there are any 'undiscovered lands" in King scholarship, at least not for this generation. I would like to see work done on his poetry-a small body of poems but really interesting in light of his novels. And he did some interesting things while a student that might illuminate his subsequent career. But he hesitates to encourage study of either. And I would like to see more solid historical criticism of his major novels-books and articles that point out, not which literary theory King uses or anything that abstract, but rather the ways in which his books describe, define, and influence our world. He is a contemporary writer-we should take advantage of that fact and work with his writings in context.

Lilja: Compared to other books about King yours are less commercial oriented and underground kind of books. They are more for research then for the average reader who is curious about King. Do you ever feel like doing a book that would be more "main stream" if you allow me to use that term. The type of book that is more likely to be bought by people that aren't die-hard King fans, people that are just a bit curious about King as a person and writer?

Michael Collings: Because I am a university professor, I don't rely on book-income for a living, so I am a bit more free in the kinds of books I write. And in the publishers I choose. I long ago decided that I had no interest in university presses that seem to survive by publishing unintelligible books on uninteresting subjects. My first book was a small monograph on Piers Anthony for Ted Dikty at Starmont House; I stayed with Starmont exclusively until Ted's death, in part because he was one of only two markets at the time for science-fiction and fantasy, in part because he was a kind man who won the loyalty of his writers. After his death, I wrote for Borgo-again, a small independent publisher, and the second of the two markets for the genre. By the time Borgo ceased publishing, Science Fiction and Horror-and King specifically-had become increasingly the province of academic publishers and popularizing presses.

I don't feel comfortable with either. The books I write are intended to allow readers to see into the books I discuss. My goal is to give those readers information and insights that they might not have (and that I might have, thanks to the fact that I can spend much more time on the books than most general readers)...and through that information to impel the readers back to the books. I write for a young audience-late high school and early college-because they are the ones who read King for pleasure; my books try to suggest ways he created that pleasure, and simultaneously suggests ways that they are literature.

Horror Plum'd, of course, differs from the others. It is strictly research, with a narrow audience, primarily intensive collectors and libraries. Most of my other books and articles, however, simply try to open new possibilities for readers.

Lilja: From what I have read of your books they are all about King's work. Have you ever considered writing a book about Stephen King; the man?

Michael Collings: No, I haven't. For several reasons. First is that others more qualified and more oriented to biography-such as George Beahm-have done excellent work in that area already. Second, I have a strong feeling about the division between public and private. A book is public; the artifact stands there, to be approached, dissected, analyzed, assessed, evaluated, and in general manipulated to the reader's content. Readers-and critics-are free to make assumptions and assertions about the book, subject only to the requirement that they have sufficient evidence from the book to verify them. Knowing something about the author frequently helps us understand a book, especially when the author is as autobiographical as King often is; but ultimately the book stands on its own, almost independent from the person who wrote it. But the person behind the book? That's something different. Since I began work on my first literary study, I've made it a practice to let the author know that I was writing a book and what kind of a books it would be. I assured them that I appreciated and enjoyed their stories (or else I would be wasting my time writing about something I disliked), and-most importantly, for me at least-assured the equally that while I might write to ask an occasional question, I would not intrude into their lives. I guess I just don't have a biographical kind of mind.

At any rate, the approach as been successful. Every writer I have chosen to study has responded graciously and openly, providing much needed information, occasionally even hard-to-find books. Some even provided bits of autobiography that might be helpful in understanding a particular passage in a book. And in return, I left them as much to themselves as I could. It was more important that they write more storied than that they answer my questions about their personal lives.

So the decision to avoid biography was conscious and carefully thought out. And I have no interest in digging any further than I have into King, the person.

Lilja: What's next for you? Are you working on anything new about King at the moment?

Michael Collings: Well, my immediate goal is to get rid of a pesky cataract so I can read easily again. That should happen by the first week in February. Then I will continue revising and rewriting two of my initial Starmont books. I've completed all but one chapter of a revised and enlarged Stephen King as Richard Bachman; it will include updated discussions of the early Bachman books and a new chapter on Desperation and The Regulators. Then I will probably finish revising The Stephen King Phenomenon, adding a new chapter or two and bringing the chapter on the bestsellers lists up to date. After that...OCP has talked about a bibliography of Dean R. Koontz. Perhaps that will be next.

Michael Collings: Well, my immediate goal is to get rid of a pesky cataract so I can read easily again. That should happen by the first week in February. Then I will continue revising and rewriting two of my initial Starmont books. I've completed all but one chapter of a revised and enlarged Stephen King as Richard Bachman; it will include updated discussions of the early Bachman books and a new chapter on Desperation and The Regulators. Then I will probably finish revising The Stephen King Phenomenon, adding a new chapter or two and bringing the chapter on the bestsellers lists up to date. After that...OCP has talked about a bibliography of Dean R. Koontz. Perhaps that will be next.Lilja: What have you written that isn't about King?

Michael Collings: As you can tell from my answers so far, I've written much that isn't about King. Starmont published my monographs on Piers Anthony and Brian W. Aldiss as well as two volumes of science-fiction/horror poetry. I've written articles about Dean R. Koontz and the only two books yet written on Orson Scott Card. I've published over 300 reviews on topics ranging from Renaissance literature to contemporary poetry; several hundred poems that have appeared in a wide range of journals; and a number of books and chapbooks of poetry. I've even published a cookbook! In addition, I am fascinated by bookbinding, and have published about a dozen books of poetry and two novels, each book hand-crafted and hand-bound. King is certainly an important part of my life as a writer, but he is not all there is.

Lilja: Have you ever met King in person?

Michael Collings: I met him once, when he was the Guest of Honor at the International Conference for the Fantastic in the Arts, held in Florida in 1984. As secretary to the association, I had the chance to meet him formally several times; as a presenter, I read a paper with him in the audience; and as a friend of a friend, I had the opportunity to spend several hours with him informally.

Then, when I began work on the Starmont series, we corresponded fairly frequently. We even exchanged books. I sent him copies of the Starmont books, and he sent me a manuscript copy of IT and a signed copy of MISERY (Gee, I wonder who got the best end of that deal?) Throughout, he was generous, kind, and open. I would send him one of the Starmont books; he would read it and respond, in time that I could include some of his comments in the next book. We were, I think, friends in a long-distance way. As his life became more complex, and the Starmont series concluded, we were less in contact. But I suppose that if someone were to mention my name to him, he would remember it, and he might even have some complimentary things to say about my writings.

Lilja: Which book by King (if any) do you think will be remembered 100 years from now?

Michael Collings: The Shining probably has the best chance of his books to date of surviving the ages. It tells a good story, and tells it in strong, memorable images. It illuminates much that was right and wrong in American culture at the times, and thus has a certain historical value. It incorporates his trademark horror, but in a rather restrained way. And it is literary, which means that it is open to being taught, especially in College literature courses. His allusions connect his story to a long literary tradition, demonstrating how he both uses that tradition and is himself part of it. If I were to expand the list, I would include Dead Zone, The Stand, and IT as his most powerful works-stories that I would hope my grandchildren might someday read and enjoy.